1 Introduction

In this presentation, I will evaluate three scales that measure ambiguity tolerance (AT) and suggest one for use in further research on Religious Education (RE). During the last 60 years, many scales of ambiguity have been developed (for an overview cf. M. Lauriola et al., 2015, 1-3 and A. Furham/J. Marks, 2013).Three examples can give a first overview of the general situation, of problems and of the decisions necessary when choosing one of them according to RE-research criteria.

1.1 How to define “ambiguity” and “tolerance”?

The Latin adjective “ambiguus” can be described in short as tilting towards two sides or as interpretable in more than one way. It can be translated as undecided, or, in relation to words, as of two (or several) meanings and, in relation to success or the outcome of a project, as open to different interpretations. (T. Baier, 2013, 282) Complex constellations, unsoluble questions, unclear social situations are phenomena that can be perceived by individuals and groups as ambiguous (for a broad overview of the existing humanities literature, see K. Wörn, 2020, 11-75).

The second term is “tolerance”. In western society, this word is used indiscriminately and frequently. As a consequence, the meaning of the word has been reduced and has become, in some cases, rather blurry. Although we cannot discuss this in depth, some short comments are necessary: The Latin term is associated with “enduring” – with rather passive implications. Some suggest “respecting” as an active term. However, in our field, the word “respecting” does not fit in combination with the word “ambiguity”.

Other combinations may be preferable: e.g. “diving” into ambiguity or “engaging” ambiguity or “managing” ambiguity (Meyer, 2021, 162-188). The advantage is that all these terms imply an active and constructive way to deal with something. To deal actively and constructively with ambiguity should be an aim of education facing e.g. diversity.

Because in empirical research, the term “ambiguity tolerance” or “tolerance of ambiguity” is used most often, I will continue to use it here. AT thus means, on the one hand, the ability to “endure” all of this, and, on the other hand, to handle ambiguities actively and constructively (“engaged”) without the urgent need, in reaction to complexity, insolubility or a lack of clarity, to commit oneself to one side or present an easy solution reducing the existing complexity.

1.2 Educational analysis

A general analysis is needed with regard to educational questions. Why is AT important as a part of didactical considerations in RE?

There are three relevant aspects, one social and two theological:

The ethical-social aspect: In our pluralistic society, we experience strangeness and sometimes uncomfortable complex situations because of cultural and religious diversity. Many people have a problem with diverse and complex situations and their lack of clarity and, thus, fall into black-and-white thinking – sometimes even demonizing religious groups. As an educational challenge in facing such processes, children and young people should learn to encounter people of other cultures and other religions respectfully, tolerating (“diving into” or “managing”) complexity or a lack of clarity in the encounter as part of religious diversity. Next to these social matters, all ethical dilemmata can be characterized as ambiguous. We summarize both aspects and assign these questions to an ethical-social level.

On a first theological level, religious issues and deeper religious thinking involve processing ambiguities to a great extent (Bauer, 2018, 34-35). They operate with suggestions for coping with the unpredictability and contingency of life, with the complexity and sometimes insolubility of many questions about God and the world. On the one hand most traditions have developed such sensitive ways of dealing with these matters, on the other hand some orthodox or fundamentalist religious movements do advocate black-and-white thinking to establish unambiguous clarity. In order to interpret theological motives in a deeper way, children and young people should be willing to face open questions in theological matters that will not find an answer on earth.

On a second theological level, talking about God or an ultimate entity is frequently connected with vague and metaphorical descriptions (cf. Bauer, 2018, 34. Experiences of a divine being are often described metaphorically. Talking about such an entity or experience is accompanied by the acceptance that there is not a clear, black and white way to express it, not just a “right” and “wrong”. Talking about “God” or forms of transcendence require the ability to endure the vague and sometimes the insoluble.[1] (Cf. the slightly different distinction of a “horizontal” and a “vertical level” in Bauer, 2018, 35 and Lorenzen in this vol.)

1.3 Procedure for testing the scales

In this essay, I would like to introduce three scales, demonstrate their advantages and disadvantages, and describe experiences in and for religious educational contexts.

We had the opportunity to test two of the scales in two very different cultural settings - in Germany (including some Swiss students) and in Hong Kong (including some people originating from Mainland China).[2]

In order to test the AT-scales for their use in RE, we took up items representing the social and theological criteria mentioned above. It needs no deeper explanation that our statistical testing of the scales does not imply that we captured all of the social and theological dimensions which may be involved. Instead, we singled out individual aspects which serve as examples.

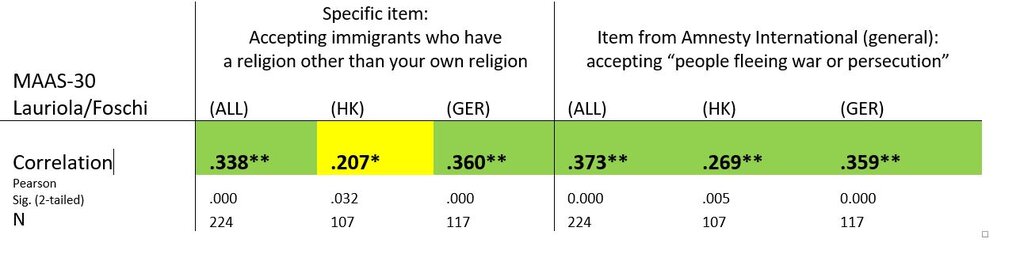

As a first criterion concerning the correlation of the AT-scales with the social level, we asked (a) about the acceptance of refugees and (b) more specific of immigrants with religious backgrounds different from one’s own. Both items are variations of items from the “Refugees Welcome Index” developed by Amnesty International.[3] P. Y. Pong developed the new items for a larger survey on refugees in schools.[4]We expected that higher AT would be accompanied by higher acceptance of these groups. That means, we calculated correlations between the AT scales and the grade of willingness to accept immigrants and refugees as an example for the social and “diversity” dimension.

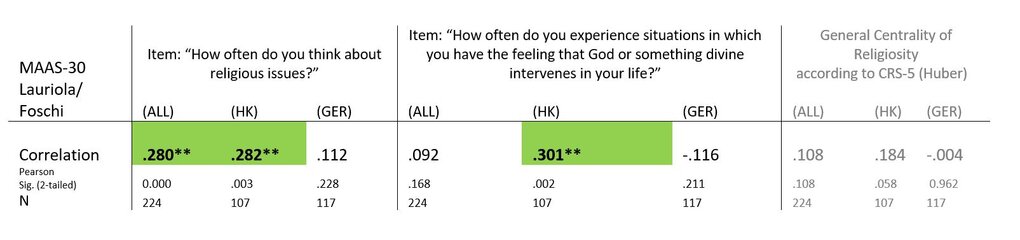

With regard to the theological aspects, we took two items from the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS) developed by Stefan Huber, which has been used in the Bertelsmann Stiftung Religionsmonitor and many other projects.[5] The first item on this scale refers to more general matters. The wording is: “How often do you think about religious issues?” (5-point-scale; answers: very often … never). It implies that many religious issues require a sensitivity for ambiguity in order to be understood in an appropriate way. Even extreme religious groups need to deal with ambiguities (e.g. concerning concepts about “god”). Facing that fundamentalist are rather rarely found in Germany, Hongkong or Switzerland, we expected that those who think more frequently about religious questions should be more used to accepting ambiguity.

The second theological item is “How often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God or something divine intervenes in your life” (same scale).

We expected that experiencing “something divine” would imply feelings and aspects that cannot be easily expressed in words. The vagueness of such experiences themselves does not necessarily lead to the ability to endure or manage it, but we expect that more frequent experiences are accompanied by the need to process ambiguity.

Both theological examples have weaknesses, but the empirical research in this field is rather limited. We could discuss how congruent they are with the criteria explained above. Surely, not all aspects are covered. However, our purpose is not to prove a special level of relationship between these matters, but rather to test if the scales of AT “react” to selected social and theological items and therefore may be applicable for use in research in the field of RE.

All items in the tested AT-scales do not have any direct connection with immigrants/refugees or thinking about religious issues/experiencing god. Nevertheless, our hypothesis is that accepting the mentioned aspect of social diversity and dealing frequently with these religious issues correlates with a higher tolerance of ambiguity.

With regard to further statistical criteria, we will concentrate on two aspects. The scales should capture different dimensions (factors) of ambiguity in general (method: Principal Component Analysis) and there should be at least a satisfying consistency of the scale (method: calculation of Cronbach’s α).

2 The first and most influential scale created by Budner

The quantitative scale with the highest influence was developed in 1960 by Stanley Budner in his dissertation, published in an article in 1962.

2.1 Budner’s concept and criticism

Budner suggested distinguishing three “types of situations” (S. Budner,1962, 34) involving “complexity”, “novelty” and “insolubility”.[6]In his 16-item questionnaire, he tested whether these aspects were avoided or desired.[7]

There is a lot to be said about this scale and its reception over the past 60 years. In short, one of the most helpful aspects of this scale is Budner’s idea to distinguish these three aspects (complexity, novelty and insolubility) and to distinguish aspects of activity with mere observations of ambiguity in the world of “perceptions and feelings” (he calls it “phenomenological”) and with aspects that may be connected with operations concerning “natural and social objects” (he calls it “operative”; S. Budner 1962, 30). This concept influenced all further scales.

Despite these advantages and despite the fact that the scale has frequently been used, there has also been a lot of criticism (cf. the critical statements of A. Benjamin et al. (1996), 631-632 and further criticism e.g. in Furnham (1994), 404):

Some items do not measure exactly what they are supposed to measure. For example, do the items “I would like to live in a foreign country for a while” or “Many of our most important decisions are based upon insufficient information” really measure AT? The longing for a foreign country may describe a desire for “novelty”, but it does not always imply the processing of “ambiguity”. The second item may derive from a general world view.

Some items were formulated in a complicated way and were barely understood by some respondents.

Later research found that the factorial structure was unclear (cf. Lauriola et al. 2015, 2).

Finally, on an empirical level, the reliability of the scale was poor. Budner himself stated that the average Cronbach’s α was just .49. (Budner 1962, 34-35, and later Benjamin et al., 1996, 626).

2.2 Translating and testing Budner

Despite the problems, we tested the scale for use in RE in international research contexts. With P. Y. Pong, I had the opportunity to incorporate Budner’s scale in a large survey with German and Hong Kong pupils (age 15-18 years N= 1976[8]and N= 831).[9] The results showed two major experiences:

Items concerning ambiguity describe situations and aspects that are sometimes difficult to express in other cultures. Translating such “complicated” aspects is a problem for questionnaires because the meaning can shift through the translation (or explanations become too long). (On the general problems of cross-cultural surveys cf. Haas, 2009)

While the German results have a reliability which is similar to the poor results of Budner (Meyer/Pong: Cronbach’s α for German questionnaires = .48, Budner: .49), the results in Hong Kong were even worse (Cronbach’s α =.12; Budner’s own worst sample: .39). This means that the Chinese scale is not consistent at all. In the analysis of the problems, we had the impression that some items were too complex and “boring” for the young people from Hong Kong.

Many problems have been reported regarding the factorial structure of Budner’s scale. Lauriola and Foschi sum it up, saying “its factorial structure still remains unclear, with proposed solutions ranging from one to five factors” (Lauriola, 2015, 2).

Because of the poor consistency in Hong Kong, we calculated the correlations with our criteria (the socially and theologically relevant items) only with the German sample (German pupils year 9-10 at secondary schools, ages primarily 15-17, entire range of age: 13-25.). The results were surprisingly good. The scale even correlated significantly with an item from Amnesty International’s Refugees Welcome Index (acceptance of people fleeing war or persecution).[10] It did not correlate with the general religiosity according to Huber’s CRS-5.[11]There was just one strange effect; the experience of something divine correlated negatively to Budner’s tolerance scale. The reason is probably that Budner’s scale reacts strongly to conservative people avoiding novelty. In his calculation, religiously conservative people are regarded as intolerant towards ambiguity because they prefer what they are used to. His scale does not react to the fact that religiously conservative people may process “theological” ambiguity in a tolerant way despite their relative intolerance of novelty. We will come back to this problem.

2.3 Summary (Budner)

Budner’s scale has the advantage of incorporating aspects such as complexity, novelty and insolubility in one scale (with normal/standard distribution – see figure above). It does correlate significantly to our social criterion and to one theological criterion. His emphasis on novelty can involve problematic results in correlating items on religious ambiguous matters. The extreme poor (and in Hong Kong unacceptable) reliability (Cronbach’s α), the problems with factor analysis and the items that are complicated to translate are serious problems.

3 Herman’s et al. scale removing insolubility

Herman et al. (2010) tried to optimize Budner’s scale for assessment in cross-cultural contexts, e.g. a survey for “expatriates” (professionals living and working outside their country of origin). I can provide only a very short impression of their analytical steps. Herman et al. analyzed Budner’s 16 items with a factor analysis, kept just 7 of his original items and added 5 more items according to their needs. The result was a scale with 12 items and a higher reliability with a coefficient Cronbach’s α of .73.

If you examine their procedure not just with mathematical tools but also analyze the contents of the remaining and new items, you find that they just kept aspects of accepting “novelty” and reduced Budner’s items of “complexity” to the aspect “clarity”; i.e. they removed all aspects of “insolubility” and explicit “complexity”[12] In a way, they reduced the three aspects of Budner’s scale (novelty, complexity and insolubility) to one and a half aspects (tolerating novelty, needing clarity). It is no surprise that the reliability turned out to have better results.

Advantage:

Herman’s et al. scale has a reasonable reliability of Cronbach’s α = .73. The reduction from 16 to 12 items is an advantage for creating questionnaires.

Disadvantage:

The “cost” is that half of the dimensions (or “types of situation” according to Budner) are dropped. Herman et al. removed coping with insolubility (including the “vague”) and major aspects of complexity. In questionnaires for expats, it may be sufficient to ask about tolerance of novelty and changes, unfamiliarity and the need for clarity. With respect to the Latin base of the word ambiguus (“tilting towards two sides”, “two meanings”), in my opinion this scale no longer measures “ambiguity”; it is mainly concerned with coping with new, unclear and unfamiliar situations, e.g. in foreign countries. There may be overlap with AT, but this is not the central aspect of tolerating ambiguity and it is definitely not adequate for religious ambiguities. Because its contents do not apply to religious subjects, we did not test the scale.[13]

4 Lauriola’s and Foschi’s scale (MAAS)

Our third example is the new scale developed by Lauriola, Foschi and others in 2015. The team took 133 items from seven older scales including Budner's items and tested them cross-culturally with US American and Italian citizens. Based on Goldberg’s approach (2006), they analyzed the “facet-level hierarchical structure” including principal component analyzes (PCA) in consecutive steps (Lauriola et al., 2015, 5). The result was a new scale with 30 items. The reliability of the new scale was analyzed with the hierarchical coefficient ω with good results. In my own calculation from our pretest, Cronbach’s α is .79 for this scale. This is a satisfying result for a multidimensional scale. The scale was called Multidimensional Attitude Toward Ambiguity Scale (MAAS).

According to a factor analysis, Lauriola and Foschi distinguished 3 factors or dimensions.

The first dimension can be described as “unpleasant feelings associated with the experience of ambiguity in interpersonal relationships, social, or job situations” (15); in my opinion, Lauriola and Foschi describe it somewhat too generally as discomfort with ambiguity (DA).

The second dimension can be summed up as black-and-white thinking or, more complexly, the “inability to allow for the coexistence of positive and negative features in the same object” (S. Bochner 1965, 394, according to Lauriola et al., 2015, 15; Lauriola et al. choose the term “moral absolutism/splitting” MA/S).

Lauriola and Foschi called the third dimension “need for complexity and novelty” (NC). In fact, it includes more facets, such as coping with vagueness and insolubility. They state that “NC appeared to most closely resemble Budner’s (1962) conceptualization of ambiguity tolerance. In our study, NC was clearly composed of two lower order facets that closely resemble characteristics today ascribed to traits such as need for cognition (e.g., engaging in and enjoying complex problems) and openness to experience (e.g., aesthetic sensitivity, novelty seeking, …)”. (M. Lauriola et al., 2015, 15)

This scale has a couple of advantages:

It was originally tested in two different languages, in English and Italian, and has just been tested in Swedish and Mandarin projects. My own tests were done in German and Cantonese (N=224). The internal consistency (with α= .79[14]) is significantly better than that of Budner and Herman et al. The content covers a wide range. If you look at the headings of the dimensions, you might not see aspects of “tilting towards two sides”. In fact, this is incorporated in two dimensions. It is rather obvious in the first dimension on social situations, and can also be found in the third dimension, hidden in the expression “aesthetic sensitivity” with items like “I tend to like obscure or hidden symbolism”, “Generally, the more meanings a poem or story has, the better I like it.”, and “Vague and impressionistic pictures appeal to me more than realistic pictures.”

A disadvantage of the MAAS is the fact that there are 30 items which is a lot for use in schools. Furthermore, the item sentences describe some rather complex situations (as in Budner’s scale). For pupils with lower reading comprehension some items are hard to understand. Unfortunately, this problem applies to all scales on ambiguity.

5 Our own experience with Lauriola’s and Foschi’s MAAS and suggestions for a shorter version

As mentioned above, I had the opportunity to pretest the scales (N=224) with participants from Germany (97), Switzerland (20) and Hong Kong (107 incl. 6 from Mainland China).[15] In contrast to Budner’s scale, I found a reasonable consistency (as mentioned) and a rather clear factorial structure.[16]

The range of age in our sample was from 14 (two cases) to 72 (one case); 50% of the sample was between 14 and 27.[17]In this pretest we had more female than male participants (68%: 31%; 1% diverse or not specified). We had 18% without religious affiliation, 3% Buddhist, 15% Catholic and 61% Protestants, 1% Taoist and 1% Muslim. This is not balanced (majority of female and protestants), but it was not the task of this pretest to represent any group of the population.

5.1 Testing the criteria

With regard to the content, we asked not only about ambiguity tolerance, but also used the criteria (mentioned above) asking about the acceptance of immigrants with other religions and religious issues with the religiosity-scale of Stefan Huber. For the “social” criterion, there is a clear correlation of AT and accepting refugees (generally) and immigrants with other religions (specifically). This correlation can be found in the German-speaking sample (GER) and in the Chinese-speaking sample (HK for Hong Kong) with only minor differences.

For the “theological” criteria, we were able to observe significant correlation only with the Hong Kong sample (and in the whole sample with the item “How often do you think about religious issues?”). There was no correlation with religiosity in general according to Huber’s CRS-5 and no correlations in the German sample.

5.2 Reducing the scale to 22 items (MAAS-22r)

As mentioned above, a problem with the MAAS is the large number of items (30) for use in schools. The complexity of the items demands steady concentration over a long period. Furthermore, significant correlations with the religious criteria in all samples would be preferable.

Considering the mathematical results and matters of content, we reduced the scale to 22 items.

We used the following criteria:

Observations in a factor analysis/principal component analysis: Calculating with three factors (according to Lauriola et al.), we had some items that did not fit perfectly in our tested sample (method see footnote 15, explained variance just 37%). The results that Lauriola and Foschi reported were much clearer. In the screeplot of the German sample, not three but four factors were options for analysis. When we calculated with four items, we found a fourth factor with three items, which we called “sticking to rules and habits/ no need for novelty”. As we have seen above (2a point 4), avoiding “novelty” does not imply rejecting “theological” ambiguity. We decided to remove three items of this factor because of content related considerations: On the one hand, items in the group “sticking to rules and habits/ no need for novelty” may be closely connected to AT. On the other hand, with regard to religion, it indicates a traditional way of thinking,[18] but not necessarily problems with the acceptance of other religions or coping with the ambiguity of experiences with an ultimate reality or dilemmata of life (traditional orthodox religious groups do deal with exactly these matters). For matters of content and in view of the German results of the factor analysis, we excluded them.[19]

There were more items with problems of content and factor analysis. The first were two items on “jokes”. A problem with “jokes” is that the concept of jokes is slightly different in different countries like China, Germany, Italy etc. Statistically, in the factor analysis, both joke items were part of the first factor, but with a rather low load (.417 and .385). We decided to remove both (perhaps a very German decision, but helpful for cross-cultural use).[20]

Another item was formulated in a rather complicated way. In fact, we found a translation in the Italian version that greatly changed the meaning, and there were problems in the Chinese translation. This was excluded as well (“I enjoy carefully rehashing my conversations in my mind afterwards.”).[21]

Because of the context of schools, an item about correct answers was excluded (“A person either knows the answer to a question or he doesn't”). This question has very specific connotations in school. Even in our sampel, Cronbach's α had a higher result, after removing it. Similarly, the item “I’m drawn to situations which can be interpreted in more than one way” turned out to be rather complicated.

In terms of content, the most important reduction was the abandonment of the aspect of novelty. A traditional way of thinking (“No need for novelty”) does not seem to be a necessary aspect of AT, furthermore religiously rather conservative persons may be automatically scored lower on the AT-scale despite the fact that they may frequently dive into ambiguous social situation (e.g. in charitable work) and deal with ambiguous, metaphoric ways to handle religious questions.

The result of this reduction for use in RE was a 22-item scale which can be handled more easily in questionnaires with youngsters (MAAS-22r).[22] Cronbach’s α of the new scale was calculated for the whole sample (α=.802) and for both samples separately (both α=.78, N=107 and 117).

As expected, the correlation of MAAS-22r and the longer MAAS-30 was very high (.961).

The new scale was tested according to our criteria as well.

In a preliminary step, we checked only the excluded items. As result, the excluded items had no positive correlation with our theological criteria.[23] In contrast to this, MAAS-22r had correlations with all criteria, including the “experience of a divine”. It is remarkable for our research that there is even a correlation with the item “participation in RE” (“How frequently did you have Religious Education as subject in school?” 4-point scale: Every year without interruption. – During most years in school – During one or some years – never).

5.3 Results of the factor analysis

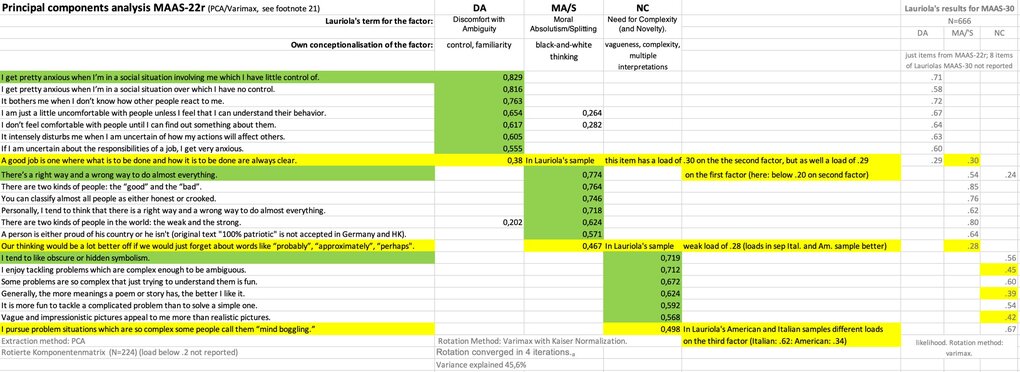

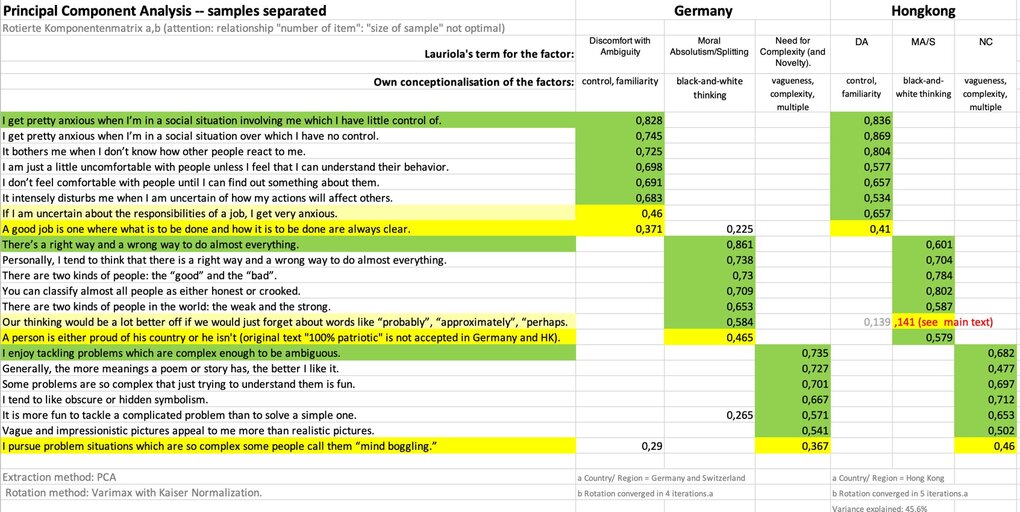

With a factor analysis (see Appendix), we found more or less the same factors in the 22-item scale as Lauriola et al.:[24]

need to control a situation/need for social familiarity (Lauriola et al.: “discomfort’” with ambiguity “in interpersonal relationships, social, or job situations …”)

black-and-white thinking (Lauriola et al.: “moral absolutism/splitting”)

coping with vagueness, complexity, multiple interpretations (Lauriola et al.: need for complexity/novelty)

Remaining weakness: Similar to the original scale, all reversed-polarity items load on factor 1 and 2. There is no diversity of polarity inside the factors. The wording of the first two items in factor 1 is very similar.

In the Cantonese sample, a deeper problem on the level of translation became obvious through the factor analysis. The item “Our thinking would be a lot better off if we would just forget about words like ‘probably,’ ‘approximately,’ ‘perhaps.’” had a load of .141 (This means that it does not really fit into the factorial structure). After analyzing the problem, it turned out that there was a problem with the dialect in Hong Kong. The translation was correct and understandable, but the words used were only used in written language and never in the daily language of native Cantonese speakers. Therefore, the expression “forgetting” the words “probably” etc. would not matter for the youngsters; they never use them in daily life because they do not write academic essays, poetry or official texts close to the Mandarin writing. In further surveys, it should be replaced by expressions closer to the dialect of people from Hong Kong.

Nevertheless, the more or less identical results in two very different contexts (Hong Kong and Germany/Switzerland) with regard to consistency and factor analysis are a strong indication that the shorter scale can be used cross-culturally for religious matters on ambiguity without major distortion.

6 Summary

The tested scales on ambiguity correlate significantly to social and religious items that incorporate relevant aspects for religious matters.

The new 22-item-scale (MAAS-22r) has not only correlations with the acceptance of immigrants “who have a religion other than your own” and the item on “think[ing] about religious issues”, but also correlations with the item “experience … divine” and with the frequencies of participating in RE.

It “reacts” on different levels and cross-culturally (Hong Kong - German speaking cultures, cf. the testing of the original version MAAS-30 with Italian and American adults). It has a distinctly better consistency than other scales (reported: Budner and Herman et al.). It is not as short as Herman’s et al. scale but incorporates 3 dimensions (a clear 3-factor structure). Therefore, I recommend MAAS-22r for further research in RE.

For translations, it is important to realize that some aspects require rather complex sentences (in a survey with young people). Sensitivity and further testing are needed for cross-cultural transfer and use in other countries.

References

Amnesty International (2016). Refugees Welcome Survey 2016. Views of Citizens Across 27 Countries. URL: https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/ACT3041002016ENGLISH.PDF [Zugriff: 03.04.2021].

Bauer, T. (2018). Die Vereindeutigung der Welt: Über den Verlust an Mehrdeutigkeit und Vielfalt. Stuttgart: Reclam Verlag.

Baier, T. (2013, Hrsg.). Der Neue Georges. Ausführliches lateinisch-deutsches Handwörterbuch, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Benjamin, A. J., Riggio, R. & Mayes, B. (1996). Reliability and Factor Structure of Budner's Tolerance for Ambiguity Scale. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 11(3), pp. 625-632.

Bochner, S. (1965). Defining intolerance of ambiguity. Psychological Record, 15(3), pp. 393-400.

Bogardus, Emory S. (1925). Measuring Social Distances. URL: https://brocku.ca/MeadProject/Bogardus/Bogardus_1925c.html [Zugriff: 03.04.2021].

Budner, S. (1962). Intolerance for ambiguity as a personal variable. Journal of Personality 30, pp. 29-50.

Frenkel-Brunswik, E. (1949). Intolerance of ambiguity as an emotional and perceptual personality variable. Journal of Personality 18, pp. 108-143.

Furnham, A. (1994). A content, correlational and factor analytic study of four tolerance for ambiguity questionnaires. Personality and Individual Differences 76, pp. 403-410.

Furnham, A. & Marks, J. (2013). Tolerance of ambiguity: A review of the recent literature. Psychology 4(9), p. 717-728.

Goldberg, L. R. (2006). Doing it all bass-ackwards: The development of hierarchical factor structures from the top down. Journal of Research in Personality 40, pp. 347-358.

Haas, H. (2009). Übersetzungsprobleme in der interkulturellen Befragung. Intercultural Journal8(10), pp. 62-77.

Herman, J. L., Stevens, M. J., Bird, A., Mendenhall, M. & Oddou, G. (2010). The Tolerance for Ambiguity Scale: Towards a more refined measure for international management research. International Journal of Intolerance Relations 34, pp. 58–65.

Huber, S. (2003). Zentralität und Inhalt. Ein neues multidimensionales Messmodell der Religiosität. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Huber, S. (2009). Der Religionsmonitor 2008: Strukturierende Prinzipien, operationale Konstrukte, Auswertungsstrategien. In Bertelsmann Stiftung (Hrsg.), Woran glaubt die Welt? Analysen und Kommentare zum Religionsmonitor 2008 (pp. 17–52). Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Huber, S. & Huber O. W. (2012). The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3(3), pp. 710-724.

Lauriola, M., Foschi, R., Mosca. O. & Weller, J. (2015). Attitude Toward Ambiguity: Empirically Robust Factors in Self-Report Personality Scales. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115577188 [Zugriff: 23.02.2022].

Meyer, K. (2021). Religion, Interreligious Learning and Religious Education. Bern: Peter Lang.

Pong, P.Y. (forthcoming PhD publication). A Correlation Study on Religiosity, Attitude towards Immigrants and Intolerance of Ambiguity and Its Implications on Religious Pedagogy: Students in Protestant Secondary Schools in Germany and Hong Kong.

Wörn, K. (2020, unveröffentlicht). Zweideutigkeit als Grundbegriff der Theologie Paul Tillichs. Verortung von Ambiguität im Verhältnis von Moderne und Religion. Jena (Diss.).

Prof. Dr. Karlo Meyer holds the chair of Religious Education at the University of Saarland, Institute of Protestant Theology

Cf. Bauer, 2018, 34: AT as a sine qua non for religion to flourish – especially concerning the need to accept transcendence as such.

For Hong Kong, P. Y. Pong was kind enough to implement Budner’s scale in her first survey (N=1979) and to help to organize the internet platform and the Chinese questionnaire for the second survey (N=224).

Amnesty International, 2016. The survey used the basic idea of the social distance scale by Emory Bogardus from 1925 copied in many variations so far.

The idea to use this new item originated from the PhD project of P. Y. Pong (Saarland University) comparing attitudes towards refugees in German and Hong Kong schools. The publication is forthcoming. The wording of the item is: “How closely would you personally accept the following groups of people? … Immigrants who have other religion than your religion …” answers “in your household”, “in your neighbourhood” … “or would you refuse them entry to your country”.

Huber, 2003. The scale has been used frequently, e.g. in Bertelsmann Stiftung Religionsmonitor. Huber later published a shorter version with 5 items: Huber, 2009.

For Budner, there are more aspects on different levels that can only be mentioned briefly. On the level of the type of responses: “phenomenological denial, phenomenological submission, operative denial, and operative submission” (Budner, 1962, 34). "Furnham (1994) tested the factor structure of several measures of tolerance for ambiguity. Budner's (1962) scale was found to measure four distinct factors: predictability (e.g., ‘What we are used to is always preferable to what is unfamiliar’), variety and originality (e.g., ‘Often the most stimulating and interesting people are those who don't mind being different and original’), clarity (e.g., ‘A good job is one where what is to be done and how it is to be done are always clear’), and regularity (e.g., ‘People who fit their lives to a schedule probably miss most of the joy of living’). These four factors were found to account for over half of the variance.” (Benjamin et al., 1996, 626)

“Intolerance of ambiguity may be defined as ‘the tendency to perceive (i.e. interpret) ambiguous situations as sources of threat’, tolerance of ambiguity as ‘the tendency to perceive ambiguous situations as desirable’” (Budner, 1962, 29).

Number of those who filled in the relevant items completely.

Survey from Nov. 2018- April 2019 in German and Hong Kong schools, form 3-5, details will be published by Pong.

To avoid confusion, we report only the negative recorded results of Budner. In fact, Budner calculated intolerance instead of tolerance. Because other scales calculate tolerance, we do it for Budner also.

Huber presented the CRS-5 as a reduced version of the original CRS-10 (Huber, 2003 and Huber/Huber, 2012); in our sample Hong Kong: α =.90 (N=107) and Germany/Switzerland α =.85 (N=117), combined sample α =.87.

Budner actually calculated the “intolerance” of ambiguity; the original results are therefore negative. In order not to create confusion, we removed the minus and left the “reverse” results. Because of the poor consistency of the Hong Kong results, only the German results are reported.

In their factor analysis, they have a new set of factors: “valuing diverse others”, “change”, “challenging perspectives” and “unfamiliarity”. These may be interesting for questionnaires for expats, but the lack of the aspect of “insolubility” seems to be a major deficit for religious matters.

In Hong Kong (N=107) α =.79 and in the German/Swiss sample (N=114) both α =.78.

he items were translated and written down in traditional Chinese characters, taking into account the Cantonese-speaking background of the respondents. Impulses from another translation in simplified Chinese for Mandarin speaking respondents (from a pilot project by Dr. Yiyun Shou) were included.

Extraction method: PCA; rotation method: varimax with Kaiser Normalization. With an alternative rotation method (oblimin) the results were more or less the same.

All Swiss and most German participants were students of theology/religion in Saarbrücken and Bern. The Hong Kong sample did not include any such students; instead, a couple of elderly persons were involved. Statistical calculations like correlation, Cronbach’s α and factor analysis were done separately for the German-speaking and the Cantonese-speaking sample. The differences will be reported.

Pong found in her project: “From Germany data, there is a significant relationship between [the religiosity of] CRS and …[Budner’s item on preference of a] regular life ... , X2 (8, N = 2110) = 34.471, p < 0.001.” Pupils “who have higher Centrality of Religiosity Scale, … agree more on the statement ‘It is preferable to live an even, regular life in which few surprises or unexpected happenings’ ” (not published draft).

The items are “I often find myself looking for something new, rather than trying to hold things constant in my life.”, “I generally prefer novelty over familiarity”, “Nothing gets accomplished in this world unless you stick to some basic rules”.

The items are “If I don’t get the punch line of a joke, I don’t feel right until I understand it.” and “I always want to know what people are laughing at.”

The Italian translation is not the same: “Mi fa sentire bene ripetermi mentalmente ciò che devo dire in una conversazione successiva.” Cantonese: “每次跟別人對話後,我都喜歡仔細地回想這個對話”.

“r” stands for the religious criteria in the process of reduction.

Two excluded items even had a negative correlation; only one of them has a positive correlation with the social criterion (acceptance of immigrants from other religions).

For methods see footnote 15; variance explained: 45,6. Only one of the items does not load on the same factor as in Lauriola's et al. sample: “A good job is one where what is to be done and how it is to be done are always clear.” In Lauriola's analysis, this item is placed at the end of factor 2 (splitting) with a minor load on factor 1 (discomfort), in our case it is placed in factor 1 (discomfort with ambiguous social situations) with no other load above .200. This observation is just a minor difference and does not need deeper interpretation.